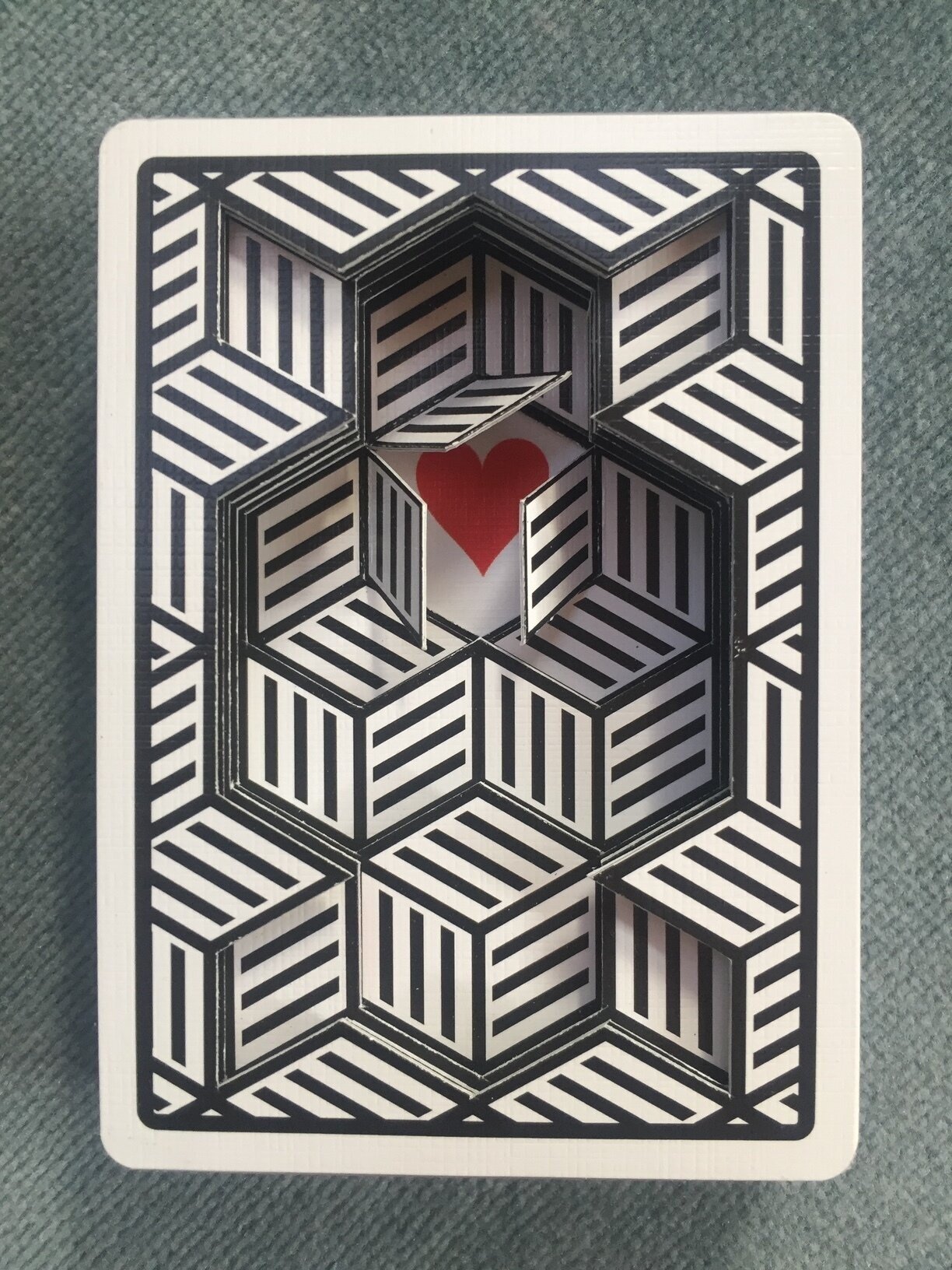

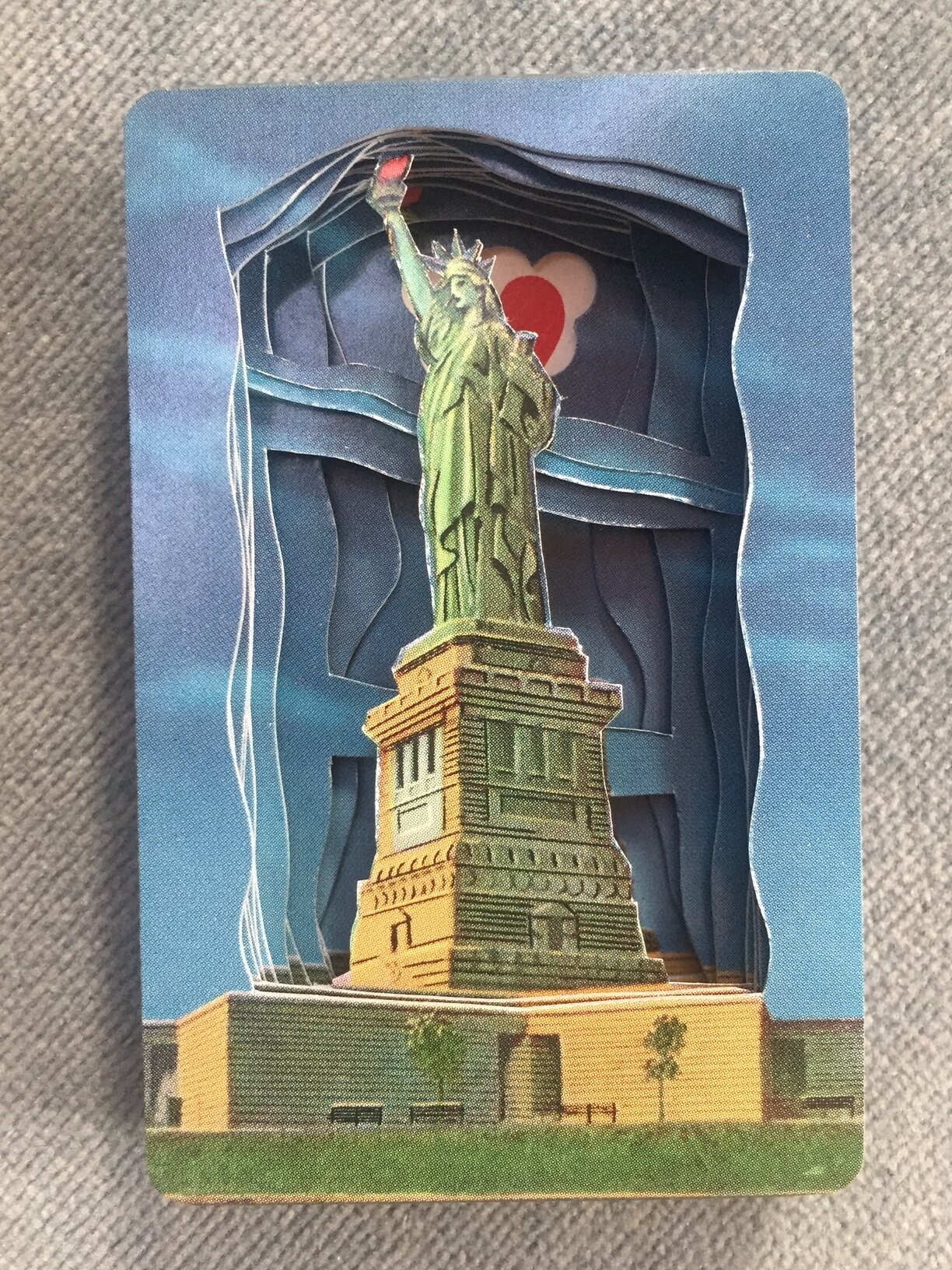

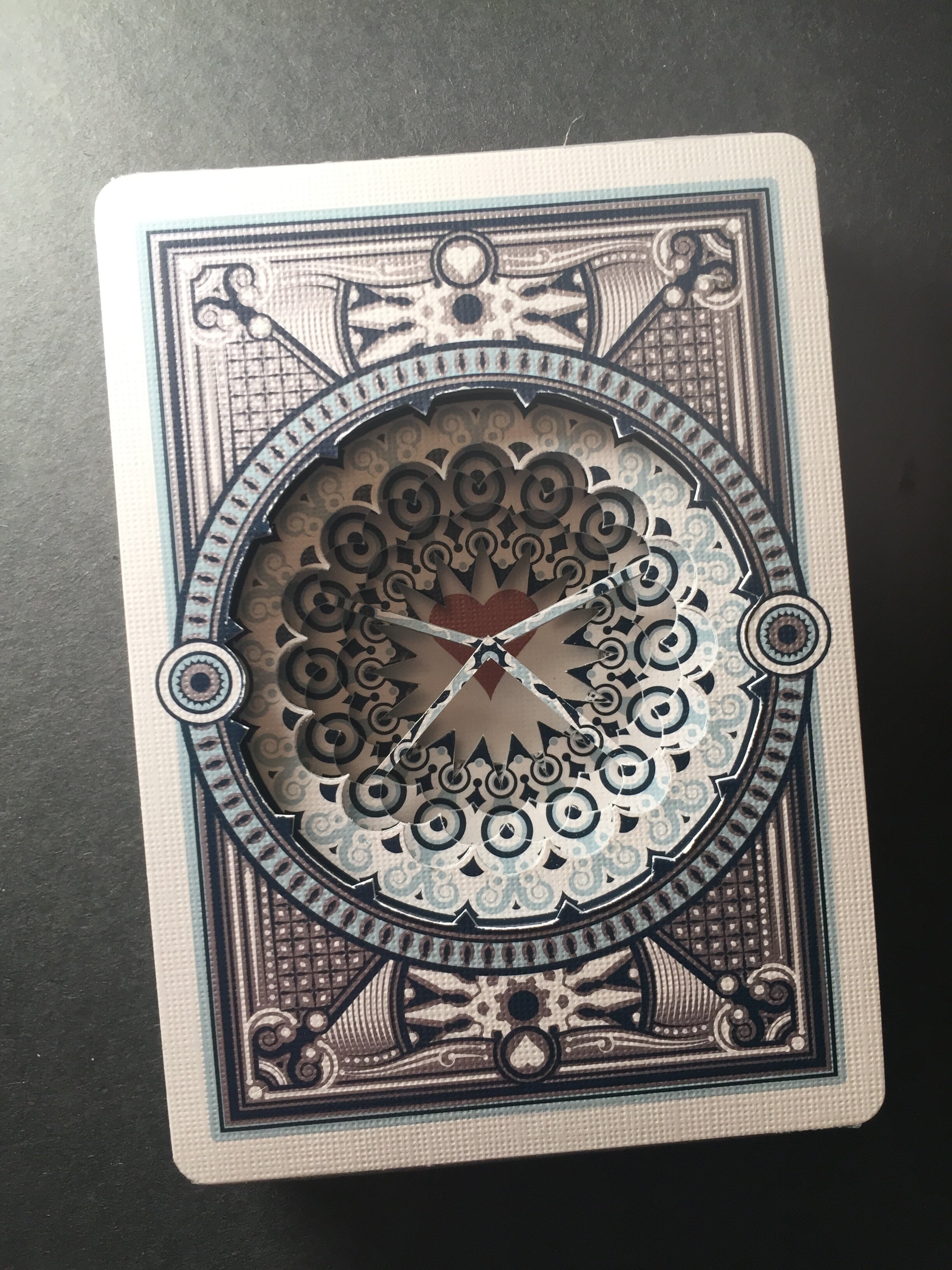

Patience is not a virtue I possess. I have a tendency to expend enormous amounts of energy in short bursts, and, if not rewarded near-instantly with tangible results, to get frustrated. This tendency is so often why I find myself in awe of artworks in which the artist’s hand is so clearly visible they way it is in Dan Levin’s painstakingly, hand-cut playing card assemblages. Playing cards themselves present a challenge in their scale alone, and the finesse required of the hand that creates meticulous slivers and snips, nicks and notches is, simply put, stunning.

Playing cards may have originated from Imperial China and the Tang Dynasty (ca. 618 AD) and the current iteration with which we are so familiar likely came to us via mid-15th century France. In a wholly modern approach, Dan Levin cuts each card by hand, excising bits of paper with an X-ACTO knife, and stacks one of top of the other to create a three-dimensional object, revealing an assembled image deep within the deck. Lonely Hearts Monarch is just one of my favorite examples of his work, and it’s my Pick of the Week.