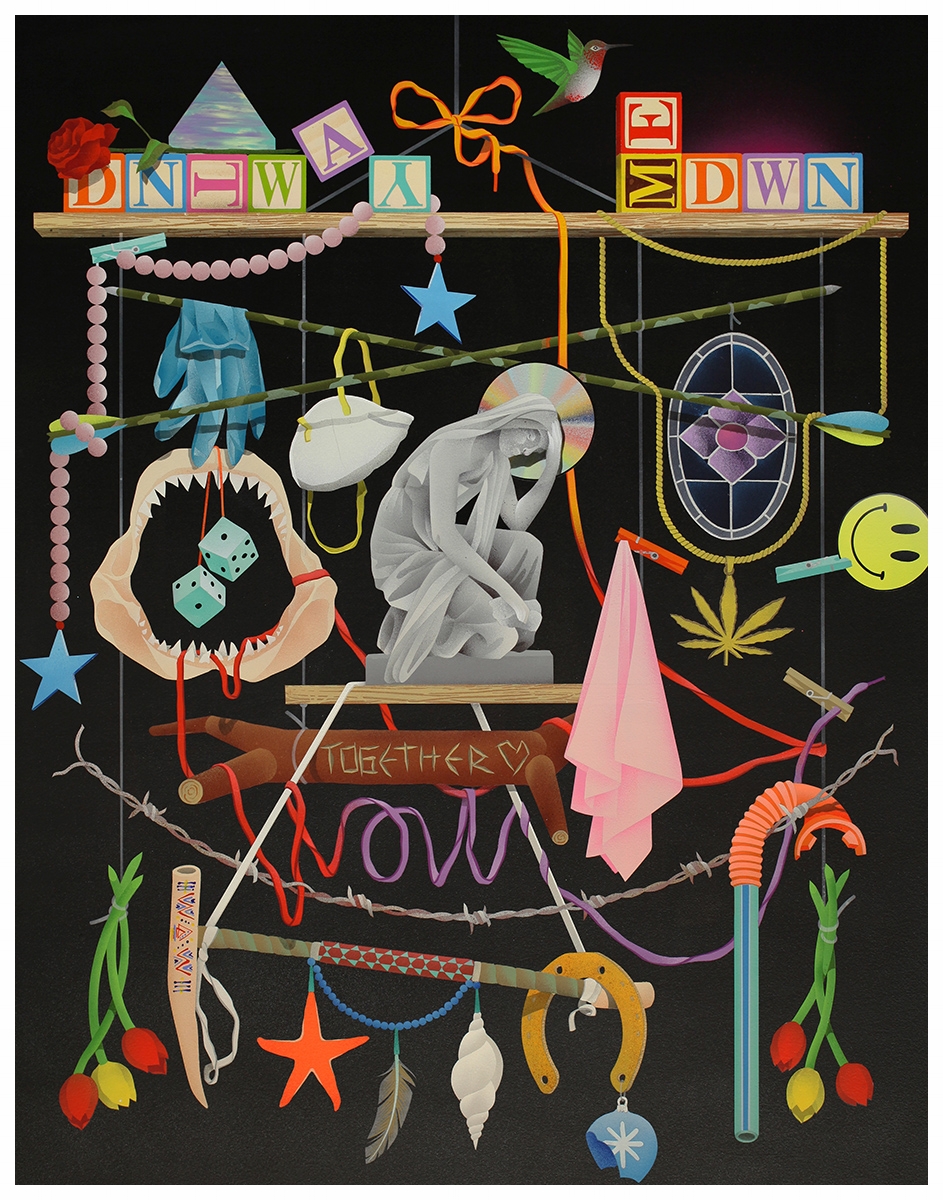

Keith. I could talk about your work, talk about you, endlessly. You are the original great equalizer. The original plays-with-his-shapes and plays-with-his-colors the way that no one has since been able to replicate. The original gone too soon. Your dance inspires me.

Keith used to dance while he painted, used to paint while he danced. The two actions intrinsic and inextricable–painting as dance, organic and involuntary. While painting any of these large scale works–a tarp, a room, a wall–Keith’d turn up the music too loud and use a single line to connect every THING to everything else. In making that line, that continuous flow of paint or ink, he choreographed a ballet and a mambo and a waltz, all at once. That line, so audacious in its boldness and its weight, became Haring’s trademark and his vehicle. The vehicle to convey the feelings that were too big to keep in and which instead he spilled out over blighted urban parks, onto subway stations’ walls, and even onto bodies. I’ve tried, on numerous occasions, to reproduce a line like that and my hand does not have the confidence of his; I stop and start too often, and despite my best efforts to control the shakes, my lines are scrabbly and scritchy. That line effortlessly expresses kindness, anger, hope, and fear, and it is legible the world over, its message language-less and simultaneously language-full. Chocolate Buddha #1 from 1989 is my pick of the week.

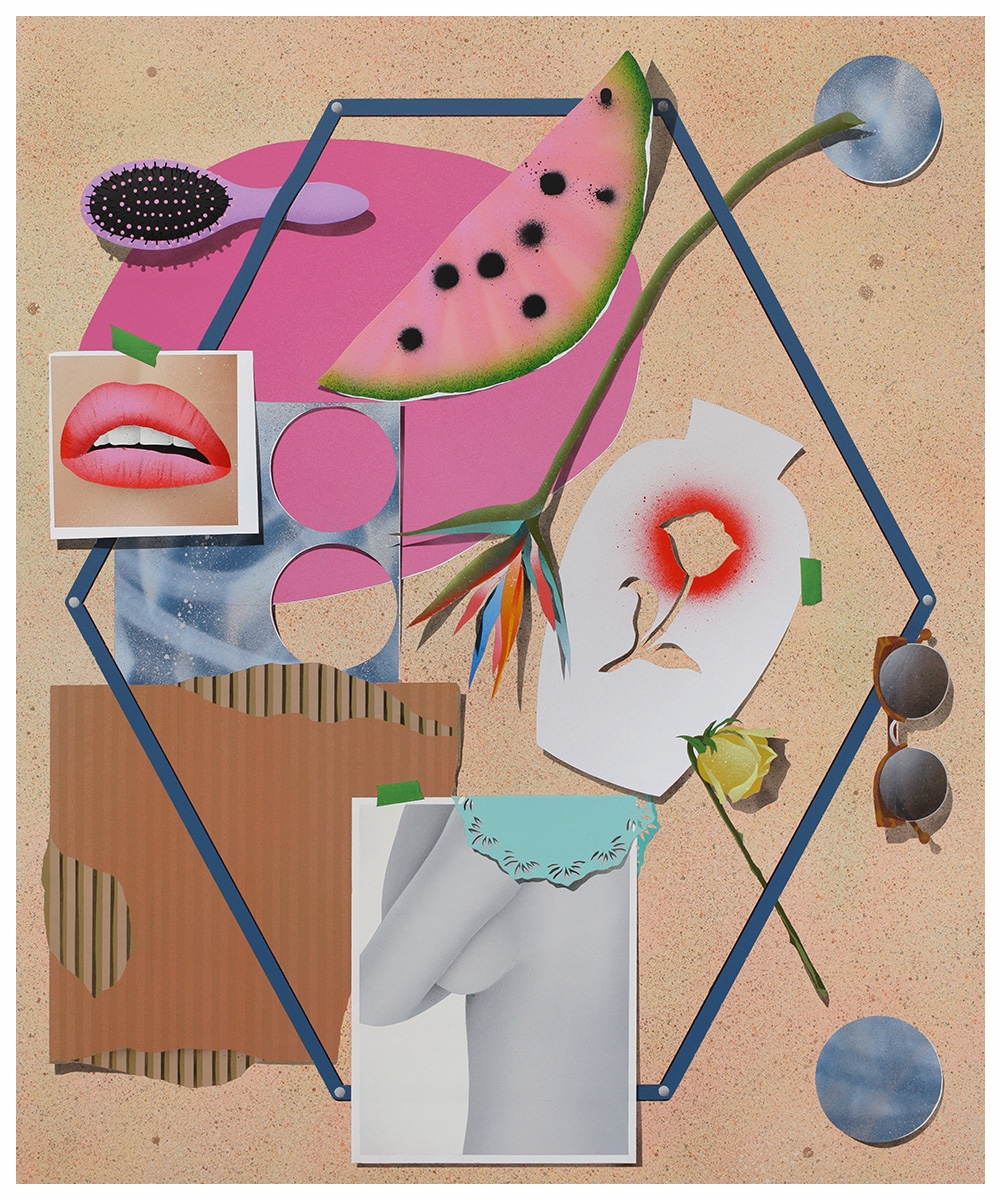

Keith Haring, Chocolate Buddha #5, 1989 | Image courtesy of bG Gallery